Mexican Spotted Owls

Are We Related?

Juvenile Mexican Spotted Owl in Refrigerator Canyon

The blistering sun in the desert of Zion National Park can be unforgiving. Hiking into a shaded and high walled canyon, like Refrigerator Canyon along the trail to Angel’s Landing, offers immediate relief from the scorching overhead heat. Temperatures drop by fifteen degrees and flowing air cools the skin, but for park biologists the lower temperatures don’t just mean relief. “Yeah, there’s probably owls there,” explains Wildlife Program Manager Janice Stroud-Settles, “they really thrive in darker mesic areas.” Janice and her team have been working since early March scouting areas where the Mexican spotted owls might be hiding.

In the 2020 Field Guide, Zion Forever supporters of all levels contributed $57,000 towards research dedicated to a deeper understanding of this federally protected species. Just months after finalizing the funding, the groundwork and collection research is complete. The next step will be sequencing and analyzing the DNA samples to gain new insights into Zion’s population.

Janice’s small research unit spent months hiking, climbing, and squeezing into remote locations on the lookout for owl activity. “We have to work relatively quickly because owl season is so short; it only runs from March through August. That’s when they are most active as far as mating and laying eggs. The eggs only incubate for around 30 days, so things can change right before your eyes.”

A lizard makes a suitable lunch for this adult

Listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1993, Mexican spotted owls, like California condors, typically mate for life. Each pairing occupies a territory, each inhabited by a separate family–– although research shows that this original definition might not be adequate according to Janice. “What we have found here in Zion is that the originally established territories may be too large. In our fieldwork at different locations we have certainly determined the need for sub-territories to better outline the realities of what we are seeing in the park. Right now our best data suggests approximately 32 known territories equating to roughly 64 birds in the park, but that data is shifting as we discover new territories that contain more than one pairing.”

Compared to other habitats outside of the park, Zion’s owls are better protected. Gazing out with distinctly chocolate colored eyes, these seldom seen raptors traditionally nest and roost in large forested areas where wildfires are their greatest threat. The birds in Zion roost in rocks and trees in tight canyons where fire danger poses a lower risk than open forests. As a result, the population inside of the park is relatively healthy and stable.

Finding the owls wasn’t easy. The researchers looked for evidence of whitewashing, pellets, and dropped feathers. Using their own voices, NPS field scientists “hoot” into the canyons seeking to solicit a vocal response from any owls eager to warn off incursions into their territory.

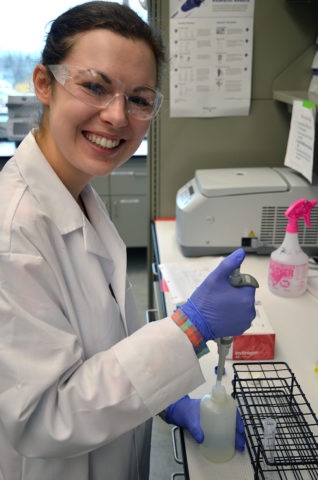

Dr. Elizabeth Flesch, Montana State University.

While the collected pellets might yield future insights into their diets and human impact, the feathers were the prize. Dr. Elizabeth Flesch, with Montana State University, is working to analyze the extracted DNA. She explains that feathers provide the best vessel to obtain clean samples. “We looked at a few different options for use in our research. The difficult part of pellets is that you have a lot of other DNA mixed in. You have the DNA of all the animals an owl has eaten, and the samples degrade so quickly when exposed to moisture and sunlight. The feathers are great because they have remnants of dried blood left from when the feather was forming, and we can target that to obtain our samples.”

She learned of the project through her mentor and colleague Dr. David Willey, a professor of Ornithology at Montana State University, who is connected with the study. He was aware of her work in genomics with bighorn sheep. “My background and research working with bighorns was very similar; even though they are very different animals we are really trying to answer the same question. How are these animals related, are they staying in the same area as their parents and having their own young, or are they spreading out seeking new areas?” In the field of genomics the level of relatedness is known as kinship. To determine this, the collected samples head into the lab. Once there, they will be processed through a battery of chemical solutions, extractions, centrifuges, and purifications before yielding a simple clean clear vile filled with pure DNA. The level of kinship may help provide answers to another hypothesis: the idea that Zion’s owls serve as a source population for other owls in the southwest region.

Dr. Flesch is excited to lay the groundwork for this unexplored theory. “If in other areas like Capitol Reef National Park we can show a connection to the owls in Zion then we can begin to understand where exactly these birds are heading. The truth is, this is really the beginning of this research. There have been other studies on mitochondrial DNA but that is only maternally inherited. Our work looks at the nuclear DNA, found in the nucleus of the cell, allowing us to observe the male contribution as well. It’s more variable and is the next step in trying to understand the population structure. We are trying to create a baseline for deeper research into these questions.”

Dr. Flesch is excited to lay the groundwork for this unexplored theory. “If in other areas like Capitol Reef National Park we can show a connection to the owls in Zion then we can begin to understand where exactly these birds are heading. The truth is, this is really the beginning of this research. There have been other studies on mitochondrial DNA but that is only maternally inherited. Our work looks at the nuclear DNA, found in the nucleus of the cell, allowing us to observe the male contribution as well. It’s more variable and is the next step in trying to understand the population structure. We are trying to create a baseline for deeper research into these questions.”

It is because of funding from our supporters that this critical research is coming to fruition. We can’t wait to share the results in a future update. Even though new funding from the Great American Outdoor Act will help to solve backlogged, deferred maintenance projects,

next-generation scientific research like this will always rely on the generous support of a chorus of voices. Scroll down to see some amazing footage captured by the NPS research team and consider adding your voice to the choir by clicking the donation link below.